The lines on Eugen Wittwer’s face are like the rings of a tree — they tell the story of a life lived subject to the whims of weather. Under his salt-and-pepper beard, the Swiss-born farmer keeps a warm smile at the ready. Putting a big glass jug into an old pickup truck outside the farmhouse on his family’s sprawling acreage near the village of Telkwa, BC, he says he needs to milk his dairy cows.

“I like my milk pasture-rized,” he quips. “They’re out in the pasture all day, every day.”

When severe drought took hold across much of Western Canada last year, many farmers saw their once-green pastures turn to barren brown deserts in a matter of weeks. As extreme heat set in, those brown fields could no longer be used for grazing livestock. Crops scheduled for late-summer harvest matured months early, causing chaos for northwest BC food producers. But Wittwer wasn’t as impacted as most — his cattle were happily grazing on greens for far longer than what seemed possible.

Since the early 2000s, he and his family have experimented with regenerative agricultural practices, using their animals to improve soil health and biodiversity. Those ways of working the land — no tilling and without chemical fertilizers — helped his soil retain what little moisture was around. The combination of mechanical tillage with chemical fertilizers and pesticides has been around for centuries, disturbing the ground and stripping the soil of its microbial life by exposing organic matter to the sun. That, in turn, leads to a greater risk of erosion and runoff, both of which are exacerbated by extreme changes in the climate.

Two decades of building up biodiversity in Wittwer’s dirt meant plant life bounced back quickly when he moved his animals to a new field.

“When we have the right soil, or the right conditions in our soil, if we get rain, it actually will infiltrate,” he says. “The rain needs to go in. It doesn’t really matter how much rain we get — it’s how much can infiltrate?”

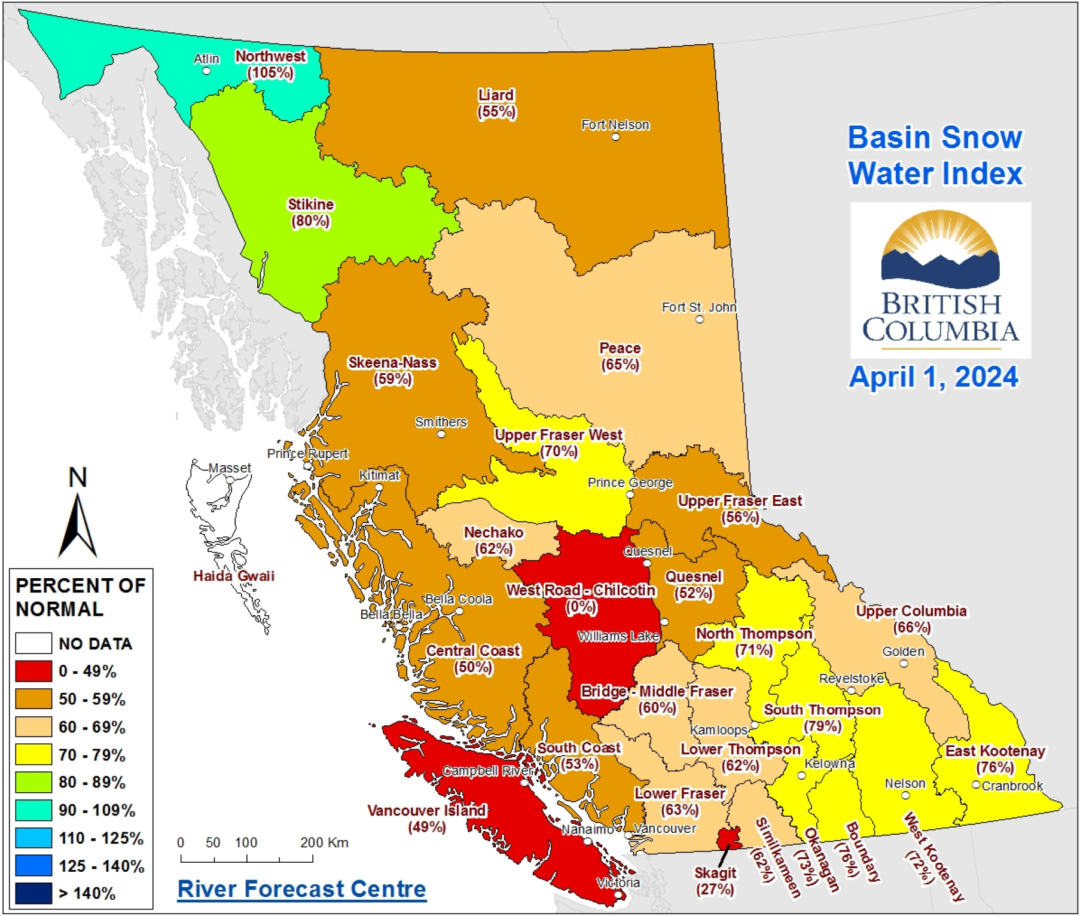

With groundwater and stream flow levels dangerously low in watersheds across BC and beyond, farmers and ranchers are bracing for another potentially disastrous season. According to provincial data, snowpack is the lowest it’s been in 50 years. That means aquifers, streams, rivers, and other freshwater systems are unlikely to recharge as things heat up this spring.

The BC government is preparing for the worst.

“The experts at the River Forecast Centre tell us these low levels and the impacts of year-over-year drought are creating significantly higher drought risk for this spring and summer,” Nathan Cullen, minister of water, land and resource stewardship, said in a recent statement.

“We know this is concerning news. Communities around BC experienced serious drought conditions last summer. It fuelled the worst wildfire season ever, harmed fish and wildlife, and affected farmers, ranchers, First Nations, and industry.”

“We’re helping farmers and ranchers with $100 million going towards new or improved water-storage systems and water-supply systems used for irrigation and livestock watering.”

Pam Alexis, Minister of Agriculture and Food

Pam Alexis, minister of agriculture and food, says the province is working closely with farmers to ensure they’re supported as climate impacts intensify.

“We’re helping farmers and ranchers with $100 million going towards new or improved water-storage systems and water-supply systems used for irrigation and livestock watering,” she says, explaining the province expects the investment will fund around 600 projects that focus on systems like dams, dugouts, and irrigation.

While government initiatives are coming fast and furious, not everyone can access the funds, and money can’t make more water. Wittwer has a 20-year head start on cultivating the conditions needed to retain rain in years of extreme drought. He’s been sharing his knowledge but says it’s not easy to convince farmers to make the switch, in part because doing so often means giving up built-in safety nets, like crop insurance, which comes with prescriptive requirements that often necessitate the use of chemical fertilizers.

As food producers reckon with an increasingly unstable climate, change of one kind or another is inevitable. And finding ways to make sure farmers and ranchers have enough water to grow crops and keep livestock alive is an existential challenge that reaches far beyond fields of cattle, pens of pigs, market greenhouses and rows of corn. After all, everyone eats.

Regenerative agriculture helps reduce impacts on the landscape — and increase yield

Last summer, Yoenne Ewald and many others across northwest BC couldn’t find enough hay to feed cattle and other livestock. As Ewald searched for a reliable source, she started thinking about selling off animals at a loss. Like others, she downsized her herd and cobbled together hay from several sources to keep her remaining animals fed through the winter.

BC’s Ministry of Agriculture says it is working to put programs into place to support farmers this year if the hay shortage persists.

“For example, we will be partnering with BC Cattlemen’s again this summer on an access-to-feed program to help those in need by sourcing available hay and matching them with sellers, whether this be in Canada or internationally,” a spokesperson with the ministry noted in an email, referring to the organization that represents a majority of beef cattle producers in BC.

Ewald says she’s working on incorporating regenerative methods so she can pasture her animals in rotating fields, decreasing dependence on hay and increasing resilience in extreme weather. But it takes time to cultivate the soil conditions Wittwer has established in Telkwa.

Last year, before the drought set in, she attended a workshop on the Wittwer ranch and has started implementing some of the techniques on her property near Hazelton. She says she wishes she had another decade without drought to encourage biodiversity and restore the land she’s farming on.

“I just feel like ten years from now, I would have been in a better position for this,” she says.

The province encourages food producers to get involved in initiatives like the beneficial management practices program and the environmental farm plan, which include promoting regenerative techniques.

“These programs provide both education and cost-share farming to encourage the adoption of regenerative agriculture practices such as reduced or minimum tillage, cover cropping, and increased biodiversity. They can also help our farmers and food producers adapt to climate change, which is the biggest challenge we face.”

“Farm something that fits your environment, something that fits into your community, fits your lifestyle, and actually fits your beliefs.”

Eugen Wittwer, Swiss-born farmer in B.C.

For Wittwer, sharing what he’s learned has become a source of joy. He started calling their operations a “community building ranch” and regularly brings in interested people to teach them his techniques.

“Farm something that fits your environment, something that fits into your community, fits your lifestyle, and actually fits your beliefs,” he says. “If you have that totally wrong, it probably doesn’t matter how much of the other ones you do. It’s probably not going to work.”

Wittwer says minimizing disturbance, be it mechanical or chemical, gives microbial life in the soil more opportunity to flourish. The richer the diversity of life in the soil, the better chance it has to develop conditions that encourage growth and retain water.

“It’s a big win-win situation,” he explains. “You can eliminate synthetic fertilizers, and there’ll be no till.”

Lastly, he says farmers need to grow a diversity of plant life and integrate animals. He points to a field pockmarked by cow patties and says grass seeds scattered on the ground there were trampled in by the animals and fertilized with their poop. He says what grows back is a wide range of plant species, which in turn promotes microbial life in the soil. As an added bonus, it’s a process that doesn’t rely on heavy machinery running on fossil fuels.

“I like to operate on new sunlight, not on ancient sunlight — that’s what oil is.”

Local knowledge is key to finding solutions to BC drought

Gazing out over his fields as cows munch on the green grass and stroll over inquisitively, he stresses the importance of context. What works for him in Telkwa isn’t going to work for a farmer in Kamloops, for example. And when it comes to solutions to problems like long-term drought, locals usually have the answers.

Mark Fisher, another farmer based in Telkwa and former elected representative of the Bulkley-Nechako regional district, says locals need to come together to support local and regional food security and are already doing so in response to wildfires, flooding and other emergencies.

“But we could add to that,” he says. “What are the food networks in our little group? These structures are in place, and we could just tweak them so that they hit all the basics.”

He adds the principles underpinning sustainable food production aren’t limited to rural areas like the Bulkley Valley.

“It can happen everywhere. It could be urban, like, it can be a community garden in the biggest city in Canada.”

Ariella Falkowski, manager of an organic farm based in Pemberton, BC, says the public needs to embrace a simple truth: climate change and the dinner table are directly linked.

When she first started producing food over ten years ago, farming was her way of facing growing climate anxiety. By making positive contributions to food security and ecological health through thoughtful, sustainable farming practices, she felt more connected to the land and empowered to protect it. But as climate disasters hit closer to home and started affecting her ability to successfully grow food, she found herself conflicted.

“Farming is getting more challenging and it’s really, really taking a toll on people’s mental and emotional health. I don’t actually want to stop doing it — it still feels good, too. But it feels more complicated than it used to.”

Ariella Falkowski, manager of an organic farm based in Pemberton, B.C.

“I started this as a way to sort of ground myself in climate anxiety and worries,” she says. “Now it’s a huge source of that. Farming is getting more challenging, and it’s taking a toll on people’s mental and emotional health. I don’t actually want to stop doing it — it still feels good, too. But it feels more complicated than it used to.”

The changing climate is inextricably linked to things like rising food costs, which means the public can help food producers in ways that aren’t as obvious as shopping at local farmers markets or signing up for a food box program.

“Ride your bike. Lobby your politicians. Those things are going to help farmers — and everyone that eats,” she says. “Tackling this climate crisis is going to support food producers.”

Cullen, the province’s minister in charge of water and lands, said the province is drawing on community knowledge to find solutions.

“We’re hosting workshops in communities around the province to help farmers prepare for drought and to connect them with financial supports,” he said in a statement. “And we’re convening regional tables in key drought-impacted areas so communities and water suppliers can use their local knowledge to develop local solutions.”

Alexis says the workshops, which included on-farm demonstrations, were aimed at helping locals navigate water restrictions, increase efficiency, and access funding.

“The goal is to ensure producers are aware of drought conditions and potential implications while helping them make more informed and timely water use decisions on their farms so they can keep producing food with the most efficient use of water,” she says.

To Wittwer, the answers can be found in the ground itself.

“If I treat the land right, it will feed me better. Healthy soil, healthy plants, healthy animals, healthy people. Simple.”

Story by Matt Simmons, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter / The Narwhal