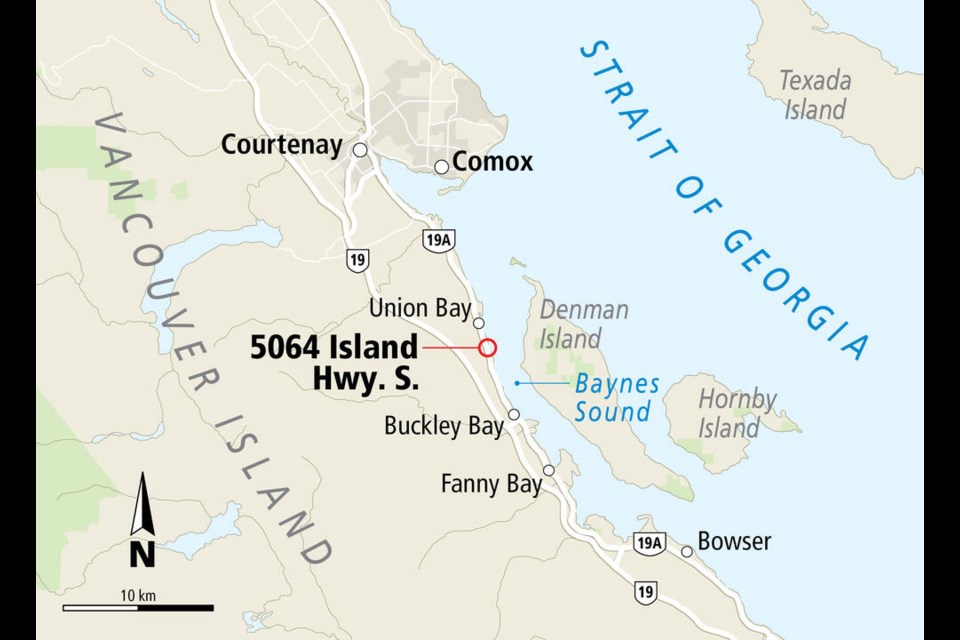

Deep Water Recovery, the company taking apart derelict vessels in Union Bay, has been hit with a pollution abatement order from the province.

The company is illegally allowing toxic effluent to run off into Baynes Sound and the marine environment, B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy has found.

“I am satisfied with reasonable grounds that a substance is causing pollution on or about lands occupied by Deep Water Recovery Ltd.”

Jennifer Mayberry, Director of Operations and Compliance for the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy.

Discharges from the ship-breaking operations are collected in sump pits, which occasionally overflow with untreated effluent. Testing of that runoff confirmed high concentrations of pollutants, including copper, iron, zinc and cadmium.

“I am satisfied with reasonable grounds that a substance is causing pollution on or about lands occupied by Deep Water Recovery Ltd,” wrote Jennifer Mayberry, Director of Operations and Compliance for the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy.

The ministry has ordered Deep Water Recovery to immediately stop the release of pollution and take additional steps to monitor and report discharges from the site. If not, the company could face penalties of up to $300,000 in fines and six months of jail time, according to the order issued on March 15, 2024.

The company has the option to appeal the order within 30 days. Deep Water Recovery director Mark Jurisich did not respond to The Discourse’s request for an interview by publication time.

“We’ve been saying this for four years, that they are contaminating Baynes Sound,” said Union Bay resident Ashlee Gerlock. She is concerned for the health of her eight-year-old son, who she lives with.

The abatement order is good news, but it’s been a long fight, Gerlock said.

“It is good news. But at the same time, it’s four years of bad news.”

The regulatory regime governing Deep Water Recovery’s operations is extraordinarily complex. Generally, the federal government manages what happens offshore, including the transport of vessels to and from the site. It also has responsibilities related to the fish habitat in the tidal waters. The province manages the company’s foreshore lease, which covers activities in the water and below the high tide mark. But the land higher up is privately owned and governed by the land use rules of the Comox Valley Regional District. The Indigenous land and water rights of the K’ómoks First Nation overlay all of this.

These jurisdictions have all been involved with policing Deep Water Recovery’s activities and responding to community members’ concerns since the company transformed the site from a log sort to a ship recycling facility about four years ago. And they’ve occasionally pointed fingers at each other for not doing enough.

On February 20, British Columbia ministers sent a letter to the federal government urging more action to regulate and respond to concerns regarding the shipbreaking site.

The Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship, Nathan Cullen, and the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, George Hayman, urged the federal government to take more action to regulate the dismantling and recycling of vessels at the site.

The letter is addressed to federal ministers for Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard, Environment and Climate Change and Transport Canada.

The provincial government is doing what it can to enforce regulations and respond to concerns in areas under its jurisdiction, the ministers write. But the federal government also has responsibilities with respect to the operations, and “we remain very concerned that Canada is not actively regulating and communicating your regulatory actions in the marine environment.”

“In a multi-jurisdictional framework such as this, it is critical that municipal, provincial, and federal agencies work together to ensure that the interests of the public, First Nations, and the environment are protected,” according to the provincial ministers’ letter.

Canada, unlike some jurisdictions, has no regulations specific to shipbreaking.

Marilynne Manning, another Union Bay resident, says that front of mind for her is action and communication from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

“What bothers me the most is the absence of the DFO,” she said, adding that she is hoping to see them come to the table on this issue.

Craig Macartney, communications advisor for Fisheries and Oceans Canada, wrote in an email to The Discourse that “our assessments did not find any pollution or hazard, either under the Wrecked, Abandoned or Hazardous Vessels Act or the Canada Shipping Act.”

He did not clarify which assessments, but included that the Canadian Coast Guard does not have jurisdiction over ship dismantling activities that occur on land.

The Canadian Coast Guard “continues to work with federal and provincial agencies that have related jurisdictions and will intervene if the situation changes and warrants intervention by the CCG,” he said.

However, documents obtained through a freedom of information request indicate that Fisheries and Oceans Canada has taken some enforcement action at the site. In 2022, DFO officials determined that Deep Water Recovery harmed fish habitat by mooring vessels and operating machines in the intertidal water. DFO ordered the company to immediately remove the three vessels grounded on the shore. At a follow-up visit a year later, one of the vessels had been brought up on shore, one had been pulled up mostly out of the water, and the third remained beached.

Samuel Lafontaine, spokesperson for Environment and Climate Change Canada, wrote in a statement to The Discourse that “ECCC is aware of the issues raised by the Concerned Citizens of Baynes Sound and takes information received from members of the public seriously. ECCC has been regularly monitoring incidents surrounding the shipbreaking facility located on Island Highway South in Union Bay, BC and has conducted on-site inspections to verify compliance with the Fisheries Act and CEPA, 1999.”

The Comox Valley Regional District has taken the position that Deep Water Recovery’s ship-breaking activities on land are not compliant with its land use bylaws. It has asked the Supreme Court of British Columbia to force the company to stop dismantling ships at the site. Deep Water Recovery denies the claim, and the matter is ongoing.

How did the vessels get there?

The provincial ministers’ letter called on the federal government’s help to stop more vessels from arriving at the site. The Canadian Coast Guard and Transport Canada would have been responsible for authorizing the towing of vessels already at the site, they wrote.

One of those vessels is the Miller Freeman, an end-of-life American fisheries and oceanography research vessel. It caught fire in Seattle in 2013, reportedly spewing toxic chemicals into the air. Then it ended up in the Fraser River, spotted in New Westminster in 2017 and Maple Ridge in 2019. After that, it ended up at the Deep Water Recovery site alongside the Surveyor, another former American research ship.

During its auction sale, the services administration confirmed that asbestos is in the Miller Freeman, identified in “pipe insulation, exhaust breech insulation, 9 X 9 floor tile, wallboard on the main deck and higher in the wallboard in the walk-in cooler.”

The services administration also warned to “not release fibres by cutting, crushing, sanding, or otherwise altering this property.”

Drone footage shows that the Miller Freeman has already been partially dismantled.

“This is a hazardous waste site. And a hazardous waste site has no business being in Baynes Sound,” said Gerlock.

The Discourse asked Transport Canada whether they could find a record of the Miller Freeman and Surveyor crossing the border into Canada.

Sau Sau Liu, a senior communications advisor for Transport Canada, said that vessels towed for recycling are typically deregistered and that “the owner was not required to obtain Transport Canada approval to tow vessels to the site.”

She confirmed that the Miller Freeman and Surveyor were deregistered, meaning they no longer fly any country’s flag.

“A deregistered vessel is not a Canadian Vessel under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, which limits Transport Canada’s regulatory authority,” she said, and included that “vessels do not have to declare to Transport Canada that they are being imported for recycling.”

Liu added that in some circumstances, federal legislation can apply.

For example, she said, “This can involve ensuring the safety of navigation under the Canadian Navigable Waters Act, or prohibitions against vessel abandonment under the Wrecked, Abandoned or Hazardous Vessels Act (WAHVA). Other federal legislation, such as the Fisheries Act, prohibits the release or discharge of unregulated contaminants into the marine environment.”

Gerlock said more needs to be done, and urgently.

“I already see the herring boats and the DFO out here. Monitoring the sound, right?” she said, citing the important herring nursery that happens here each March.

“It needs our protection; our federal government says it needs to be protected. And then they go and allow this.”

Story by Madeline Dunnett, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter / The Discourse